The Pursuit of Excellence in the Double Pole Technique

by Marianne Osteen, PSIA-RM Cross Country Education Staff

As cross country skiers, instructors and athletes, we are continually looking for ways to improve our ski performance. Although we usually ski “just for fun”, we are often striving to develop more speed, endurance and efficiency. We may choose to focus on one specific component of our skiing fitness such as aerobic capacity, anaerobic threshold, or strength. At other times, we may choose to focus on our skiing technique including proper body positioning, efficient movement patterns, and proper timing. In this article, I make the case for the pursuit of excellence in the double pole technique. I believe that mastering the double pole is one of the most important and efficient ways to improve your overall skiing performance. First, I will give some reasons why the double pole motion is important in both classic and skate skiing. Next, I will discuss some current research on physiological and technical aspects of double poling. And finally, I will offer some ideas on how to improve your double pole technique. Within this analysis, I will offer some of my own general impressions acquired while skiing, teaching, and coaching skiers. These ideas are relevant to skiers of all levels from the beginner to the elite and apply to both classic and skate disciplines.

Developing a strong and efficient double pole is obviously important in classic skiing. It is often faster and more efficient than the diagonal stride even on uphill sections of trail depending on snow conditions. We have seen an increase in the use of this technique by elite skiers who sometimes double pole entire races without any kick wax and often finish at the top of the field. The kick double pole in classic skiing is another obvious application of the double pole motion, but with the addition of a strong single leg kick for each pole stroke. Perhaps not as obvious as in the classic techniques, the V2 and V1 skating techniques incorporate the double pole motion as well. The V2 technique applies the same upper body motion as in the double pole technique, and uses all of the same muscle groups. The slight variation of the stroke in the V2 occurs as the skier balances over one ski at time, and applies the double pole pole stroke in coordination with the push off from each ski. Similar to the V2, the V2 alternate skate technique uses the double pole motion except with only one pole stroke for each skate cycle. During the V1 technique, the arm position is off-set, but if you observe the motion of the upper body, you will see the same powerful double pole motion. Not only is the double pole incorporated within these skate techniques, but there are times when an extended double pole may be used during a skate ski session. I often double pole for an extended time if my legs need a break from the skate motion or when the skate lane is not as fast as the track. So we see that across all classic and skate skiing techniques, a well developed double pole is applicable and beneficial to skiing performance.

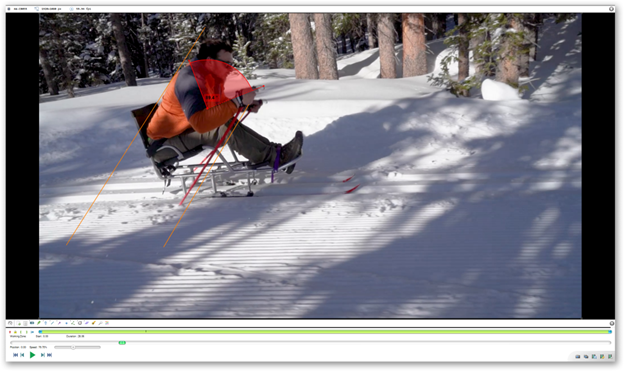

V2 skate technique incorporates double pole motion. Photos by Linda Guerrette courtesy of PSIA-AASI

Over the past several decades, the double pole has evolved into a more compact and powerful stroke compared to the double pole of the past. I will describe some general points of this more compact form of double pole. The hands and hips come upward and forward together with the elbow joint maintained at 90 degrees or less in the forward high hand position. The arms do not reach forward, rather the whole body angles forward from the ankles. As the body weight is planted on the poles, the skier uses a dynamic whole body movement contracting muscles of the trunk, lower body, and upper body to create propulsion through the poles. When a skier performs a coordinated and skillful double pole, the whole body resembles a spring loaded and then released with each powerful stroke.

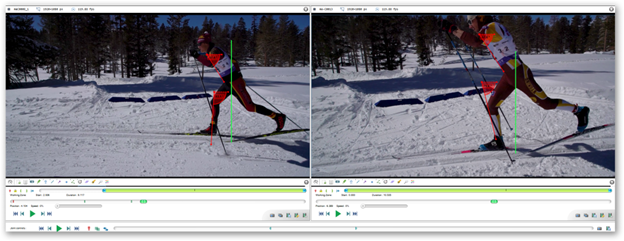

Double pole at the start of pole stroke (showing “high” hands and hips). Photo by Linda Guerrette courtesy of PSIA-AASI

Double pole at the end of pole stroke (showing flexion of ankles, knees and hips). Photo by Linda Guerrette courtesy of PSIA-AASI

Within the double pole technique, there are variations in both form and tempo depending on the terrain, speed, and fitness level of the skier. In both the uphill and the accelerating double pole, the hands generally do not follow through beyond the hips because of the shorter time of the skiing cycle. As the hill becomes steeper, the body mechanics continue to become more compact with a shorter and quicker pole stroke. During faster flat and downhill double pole sections, both the ski glide and the follow-through with the hands become longer as the duration of the skiing cycle increases. In some cases of this longer glide double pole, the hips will rise up slightly ahead of the hands in order to maintain a rhythmic motion. This connection between push-off and glide is visually represented in the PSIA XC technical model where push-off, weight transfer and glide interrelate to create continuous forward motion. If the timing changes for the glide phase, the timing will necessarily change for the push-off phase.

An interesting study (Stoggl and Holmberg, 2016) compared the kinematics and kinetics of the double pole technique performed on flat and uphill terrain. During uphill double pole, swing times were shorter (quicker tempo) and peak pole forces greater. The shorter swing time translates to less follow through of the hands. During the uphill double pole, the angle of the elbow joint was more flexed and the shoulder joint less flexed resulting in the arms remaining closer to the torso. The knee was more flexed, but there was less flexion in the hips keeping the torso more upright. Skiers raised their center of mass 25% more during the uphill double pole and obtained maximal heel rise closer to the timing of the pole plant. The primary observations from this study were that in the uphill double pole the tempo was higher, the range of motion for all joint angles was less, the torso was more upright, and more force was applied through the poles. During higher speed terrain sections such as slight downhills or flats, the skiers decreased stroke tempo, allowed more movement through the shoulder, elbow and hip joints, and increased follow-through with the hands. From a recreational skier’s point of view, if the goal is simply an easy ski day, the relaxed slower tempo double pole will be the preferred technique variation.

Many skiers believe the double pole is predominantly an upper body exercise, however, an interesting study (Holmberg et al., 2006) evaluated the contribution of the lower body to the total workload of the double pole by restricting motion of the knees and ankles. The study compared several physiological markers as well as maximal speed achieved for elite skiers under two conditions. All variables were measured for the skiers double poling with either “locked” or “free” knee and ankle joints. The results showed that when the knee and ankle joints were free to move during maximal double poling, skiers achieved a higher maximum velocity, higher VO2 peak, and a longer time to exhaustion. This study emphasized that the coordinated movements at the knee and ankle joints are an essential part in the development of a skillful double pole. In other words, the double pole technique is a whole body movement.

Another recently published study (Dahl et al., 2017) measured more precisely how the work of double poling is distributed between the upper and lower body. This research was performed by Jorgen Danielsen who studied the double pole technique as part of his PhD dissertation thesis while a student at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. An excellent article published in Norwegian SciTech News (Sliper, 2018) contains a review of his original research.

Danielsen compared double poling on flats, moderate inclines and steep inclines at varying intensities. He found that when double poling at lower-intensity about 60% of the total work comes from the upper body and 40% from the lower body. As the intensity and incline increase, more work comes from the lower body until about 50% comes from each. This lower body work occurs primarily during the recovery phase as the extension of ankles, knees and hips bring the body upward and forward in preparation for the next pole stroke (Danielsen et al., 2015).

Danielsen emphasized that although the lower body contributes 50% or more of the work, the upper body needs to be strong enough to perform the double pole efficiently. From my experience coaching skiers and from my own training, I have observed that when significant core and upper body strength has been developed through strength training or participation in other sports, an efficient double pole technique can be acquired without difficulty.

We have seen that the double pole motion is used in virtually all techniques of both classic and skating, and we have examined some of the technical aspects of how the double pole is performed. Now, the question may be asked, how do we develop a stronger and more efficient double pole in order to gain maximum benefits to our skiing performance?

First, we need to have a sufficient level of overall body and core strength in order to develop proper on-snow technique. After these strength prerequisites are achieved, specific on-snow training will yield optimum benefits. A year round strength training program that moves from general to specific and varies throughout the year is best. If you are new to strength training, I would advise seeking out the guidance of a strength training professional to ensure proper development and prevent injuries. There are many exercises that can be done using only bodyweight if you are not inclined to the weight room.

With sufficient general strength, the next step is to work with a ski instructor or coach to develop proper technique. Without proper technique, you will train and ski below your potential and more importantly, without proper technique there is an increased possibility of overuse injuries. Being forced to take time off due to injuries is something we definitely want to avoid.

Finally, you can incorporate on-snow specific training including long distance double poling sessions (endurance training) and shorter interval sessions (sprint training) over varied terrain. The foundation of moderate intensity endurance double pole sessions should be developed before adding intensity in the form of short interval type sessions.

A recent study (Vandbakk et al., 2017) compared the effects of adding either sprint interval training or continuous double pole training to the regular training of female cross-country skiers. Both training groups showed significant improvements in double pole peak speed and VO2 peak, as well as in upper body strength and power. In general, we see that both long moderate intensity double pole sessions and short sprint double pole sessions offer benefit to the skier.

Here are a couple of ideas for specific double pole training on snow:

1. Long distance double pole sessions (one time per week).

Warm-up easy skiing for 15 to 20 minutes. Double pole only (low to moderate intensity) over varying terrain. Start with a manageable but challenging amount and build from there.

10 to 20 minutes is a good starting point, but keep it within your comfort zone and ability.

Be aware of good form with each stroke and finish before you lose form. Cool down easy skiing.

2. Interval Sessions (one time per week)

These sessions can be incorporated into your training after you are comfortable with moderate intensity over distance. Short sessions build speed, adaptability, and extra strength.

Always warm-up and cool down with easy skiing for 15 to 20 minutes.

Each work interval should be approximately 15 to 30 seconds with a 1:4 work to rest ratio. (For example, 15 seconds accelerate to maximum speed with 1 minute easy ski recovery.)

4 to 6 repetitions is a good starting point working up to 8 to 10 repetitions over several weeks. After adapting to flat terrain, you may wish to try these short sprints on an uphill to vary your body mechanics. Again start with a comfortable number of repetitions. There are many ways to vary interval workouts, and if you are interested in this type of training, a ski coach is always a good option.

Whether you are skiing just for fun, fitness, or competitive achievements, the double pole technique is an important skill to master and deserves your attention. A well-developed double pole will add strength to all of your skiing techniques. Developing a general foundation of overall body strength, becoming skilled in the double pole technique, and acquiring specific double pole fitness will accelerate you to the next level of excellence in skiing.

References

Dahl, C., Sandbakk, Ø., Danielsen, J., & Ettema, G. (2017). The Role of Power Fluctuations in the Preference of Diagonal vs. Double Poling Sub-Technique at Different Incline-Speed Combinations in Elite Cross-Country Skiers. Frontiers in physiology, 8, 94. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00094.

Danielsen, Jørgen et al. “Mechanical Energy and Propulsion in Ergometer Double Poling by Cross-country Skiers.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise vol. 47,12 (2015): 2586-94. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000723.

Holmberg HC, Lindinger S, Stöggl T, Björklund G, Müller E. Contribution of the Legs to Double-poling Performance in Elite Cross-Country Skiers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006 Oct;38(10):1853-60. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000230121.83641.d1.

Midling, A. S. (2018, February 20). Proper poling technique can decide Olympic winners.

Norwegian SciTech News.

https://norwegianscitechnews.com/2018/02/proper-poling-technique-can-decide-olym pic-podium-position/.

Stöggl TL, Holmberg HC. Double-Poling Biomechanics of Elite Cross-country Skiers: Flat versus Uphill Terrain. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016 Aug;48(8):1580-9. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000943.

Vandbakk K, Welde B, Kruken AH, Baumgart J, Ettema G, Karlsen T, Sandbakk Ø. Effects of upper-body sprint-interval training on strength and endurance capacities in female cross-country skiers. PLoS One. 2017 Feb 27;12(2):e0172706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172706.